In Nova Scotia's CEN-2 zoning, developers face a choice between tall mid-rise (4–6 storeys) and tower (7+ storeys) designs. Here's what you need to know:

- Tall Mid-Rise: Lower construction costs ($160K–$200K/unit), faster timelines, and simpler wood-frame structures. Best suited for FAR caps of 2.25–4.0.

- Towers: Higher costs but maximize unit density under FAR caps of 5.0–8.0. Require concrete/steel construction, advanced elevators, and deeper foundations.

- Parking: Options include underground (costly but space-efficient), surface (cheaper but land-intensive), and podium (balanced). Underground parking can cost up to $105K per stall.

- Construction Model: Integrated design-build is faster and avoids cost overruns common in fragmented approaches.

- Rental Returns: Mid-rise projects often yield 12%–20% annual returns, while towers offer higher income potential due to greater density.

Quick Comparison:

| Feature | Tall Mid-Rise | Tower |

|---|---|---|

| Storeys | 4–6 | 7+ |

| FAR Suitability | 2.25–4.0 | 5.0–8.0 |

| Construction Cost | $160K–$200K/unit | Higher due to complex systems |

| Parking Costs | Surface: $4,350–$10,500/stall | Underground: $50,750–$105,000/stall |

| Rental Income | $25,200/month (12 units) | $37,800/month (18 units) |

| Timeline | ~6 months with integrated approach | Longer due to complexity |

Choose tall mid-rise for lower costs and quicker builds, or towers for maximizing density and long-term returns. Your decision depends on FAR caps, budget, and investment goals.

CEN-2 FAR Caps and Zoning Rules

CEN-2 FAR Limits and Requirements

CEN-2 zoning is one of Nova Scotia's most intensive development categories, tailored for high-density, mixed-use projects. Within the Centre Plan framework, these zones allow for Floor Area Ratios (FAR) ranging from 2.25 to 8.00, offering greater flexibility compared to CEN-1 zones, which are capped between 1.75 and 3.50[1].

Height restrictions in CEN-2 zones permit buildings up to 90 metres (roughly 29 storeys). However, this height must align with the FAR cap for the site, ensuring that while developers can build taller structures, the total floor area remains within the allowable limits[1][2].

CEN-2 zoning is part of the Centre Plan's strategy to support growth in the regional centre. The plan aims to accommodate 40% of the region's total growth, with projections from 2017 estimating the addition of 18,000 new residential units and 33,000 residents over 10 to 15 years[2]. This could lead to a population increase of 2.5 times in the regional centre[3].

For those planning multi-unit developments, understanding where your property falls within the 2.25 to 8.00 FAR range is critical. These limits directly impact the design and scale of potential projects, as explored below.

How FAR Caps Affect Building Design

The FAR caps in CEN-2 zones play a significant role in shaping building designs, influencing whether a property is suited for a mid-rise or high-rise structure. By multiplying the lot size by the applicable FAR, developers can calculate the maximum allowable floor area for their site.

For properties with lower FAR ratios (about 2.25 to 4.0), a tall mid-rise design, typically four to six storeys, may be the most practical choice. This approach avoids the additional costs associated with high-rise construction, such as specialized structural systems, elevators, and fire safety measures.

On the other hand, properties with higher FAR ratios (around 5.0 to 8.0) are better suited for tower designs. The larger allowable floor area in these cases can offset the added complexity and expenses of high-rise construction, making vertical designs a more viable option under these conditions.

Structural Requirements: Towers vs Tall Mid-Rise

Structural Design Differences

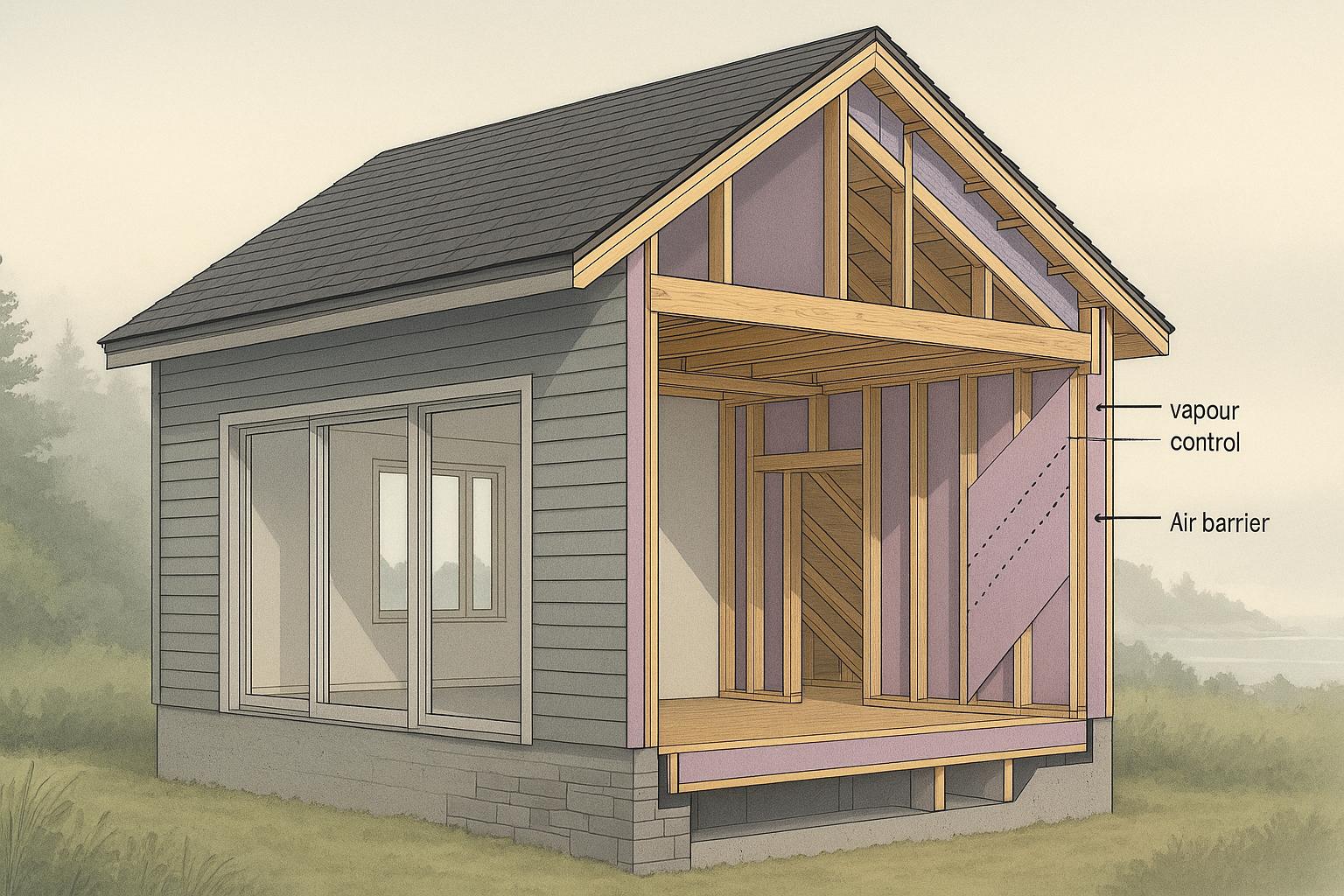

When it comes to structural systems, towers and tall mid-rise buildings take very different approaches, especially under CEN-2 FAR constraints. Tall mid-rise buildings typically rely on wood-frame or hybrid construction. These methods use familiar components like conventional foundations, load-bearing walls, and standard concrete footings. To handle lateral forces - think wind or moderate seismic activity - builders apply standard bracing techniques and connection details.

Towers, however, demand a more robust setup. They often feature a reinforced concrete core combined with either a concrete or steel frame system. This concrete core isn’t just for stability; it also houses elevator shafts, mechanical systems, and acts as the structural backbone. Foundations for towers are usually deeper or more specialized, and seismic design enhancements are often part of the package to handle the challenges of greater height. Naturally, these structural differences have a big impact on both costs and construction timelines.

Construction Cost and Timeline Differences

The choice of structural system directly influences how much a project costs and how long it takes to complete. Tall mid-rise buildings tend to be more predictable in terms of pricing. Their construction phases often overlap, which helps speed things along and keeps timelines relatively short.

Towers, on the other hand, come with added complexity. This complexity translates into higher costs and longer schedules. For instance, tower construction often involves sequential processes like multiple concrete pours, each requiring curing time. Add to that the need for specialized equipment, and it’s easy to see why these projects demand more time and money.

Elevator Systems and Code Requirements

Elevator Design and Requirements

In Nova Scotia, passenger elevators play a key role in ensuring accessibility between levels, as specified by the Nova Scotia Built Environment Accessibility Standard Regulations, set to take effect on March 6, 2025 [4]. The technical aspects of elevator design and operation in both towers and taller mid-rise buildings are strictly regulated by the Nova Scotia Building Code Regulations [4]. These guidelines set the stage for discussions around accessibility and regulatory compliance.

Accessibility and Building Code Compliance

In addition to technical standards, residential buildings with four or more units are required to display emergency evacuation plans near main entrances. These plans must include specific procedures for assisting individuals with disabilities [4]. Adhering to these requirements is essential for meeting regulatory standards and ensuring the safe operation of elevators.

Parking Solutions and Site Layout

Parking Design Options

When working within CEN-2 FAR caps, developers have three main parking design options: underground, surface, and podium parking. Each comes with its own set of trade-offs. Underground parking saves ground-level space but comes with steep costs. Surface parking, on the other hand, is more budget-friendly but requires more land. Podium parking strikes a balance between the two, though it demands careful planning for ventilation and accessibility. These choices inevitably shape both the financial and environmental aspects of a project.

Parking Cost and Access Considerations

The type of parking design chosen has a major impact on project costs and sustainability. For example, in Vancouver, underground parking costs range from $160 to $250 per square foot, while in Toronto, the price climbs to $175 to $300 per square foot. In contrast, surface parking is far more economical, costing only $12 to $25 per square foot in Vancouver and $15 to $30 per square foot in Toronto [5]. This means underground parking can cost anywhere from six to 20 times more than surface parking.

To put it into perspective, each parking stall - factoring in access lanes - requires about 27 to 32 square metres (290–350 square feet). At Toronto's underground rates, a single stall could cost between $50,750 and $105,000, while surface parking costs range from just $4,350 to $10,500 per stall.

"Before Toronto rolled back mandatory minimum parking requirements, you were seeing … lots of buildings where they had way more parking than anybody wanted. People just wouldn't claim them, and they have to be absorbed, in general, by the costs in the building."

- Shoshanna Saxe, University of Toronto [5]

Beyond costs, environmental factors also play a critical role in parking decisions. Underground parking construction involves extensive soil excavation, often releasing trapped CO₂ and increasing the building's carbon footprint. By reducing the number of underground parking spaces by just 10, developers could cut CO₂ emissions by 50 to 8,500 tonnes [5]. To put it in perspective, building a single underground parking space can generate emissions equivalent to the annual output of an average car.

"For each level of parking you remove, you can reduce the [greenhouse gas emissions] of a building by about 15 per cent. The simplest, easiest thing you can do to make your building more sustainable is not have a whole bunch of underground parking."

- Shoshanna Saxe, University of Toronto [5]

Shifting lifestyles are also influencing parking needs. Many municipalities in Nova Scotia are rethinking mandatory parking minimums, as trends like ride-sharing and remote work have led to a reduced demand for parking overall.

Construction Delivery: Integrated vs Fragmented Approaches

Problems with Fragmented Construction

Fragmented construction involves coordinating a host of independent professionals - architects, engineers, general contractors, and subcontractors - each with their own priorities and workflows. This setup often leads to serious coordination headaches. For instance, when architectural and engineering plans don’t align, the responsibility to resolve these conflicts typically falls on the property owner, who may lack the technical know-how to navigate such issues.

Budget overruns are almost a given with this model. Cost-plus contracts frequently shift financial risks onto property owners, with costs inflating by as much as 30% to 60%. When problems arise, teams often point fingers at one another, leading to delays and additional expenses. The absence of a single accountable party also undermines quality control. Structural defects, mechanical issues, or finishing problems might only surface months after the project is completed, making repairs costly and complicated.

These challenges highlight the stark difference between fragmented construction and the integrated design-build approach.

Advantages of Integrated Design-Build

The integrated design-build model solves these issues by consolidating planning, architecture, engineering, and construction within a single organization. Instead of juggling multiple contracts and managing competing interests, property owners partner with one company that takes full responsibility for the entire project.

For instance, Helio Urban Development offers a guaranteed 6-month construction timeline, with delay penalties of up to $1,000 per day. This commitment is achievable because all project components are handled in-house. Fixed-price contracts - set at $160,000 per unit for standard builds or $200,000 per unit for CMHC MLI Select qualifying projects - ensure property owners know the exact cost upfront. This streamlined approach has consistently delivered projects with zero cost overruns.

Advanced scheduling tools play a crucial role in maintaining efficiency. These systems enable seamless coordination, cutting typical construction timelines from the industry standard of 12–18 months down to just 6 months. Quality is assured through triple verification, which includes five engineering inspections and a final review selected by the owner, all backed by a 2-year warranty.

Transparency is another key benefit. Property owners receive daily photo updates and access to a real-time project portal, keeping them informed every step of the way. Faster project completion also translates to quicker rental income. For example, a fourplex with units renting for $1,950 to $2,100 per month can start generating revenue much sooner, avoiding delays tied to extended final inspections. This accelerated timeline can make a significant impact on first-year earnings.

sbb-itb-16b8a48

Rental Returns and Project Feasibility

Cost Per Unit and Rental Income

When comparing upfront costs and long-term rental returns, towers and tall mid-rise buildings under CEN-2 FAR caps show distinct differences. In Nova Scotia, tall mid-rise units typically cost between $160,000 and $200,000 per unit. These lower costs are due to simpler structural designs, standard elevator systems, and more straightforward parking solutions.

Towers, on the other hand, come with higher per-unit costs because of their more complex systems. However, they compensate by maximizing the number of units, which helps balance the added expenses. In Halifax's CEN-2 zones, current rental rates for well-designed two-bedroom units range from $1,950 to $2,100 per month. For example, a 12-unit tall mid-rise could generate about $25,200 in monthly rental income, while an 18-unit tower on the same plot might bring in approximately $37,800 per month. This additional income potential makes the higher construction costs of towers more justifiable over a 10- to 15-year investment period.

By adopting an integrated design-build approach, construction timelines can shrink from 12–18 months to just 6 months, allowing for faster rent collection and boosting first-year returns. These cost and revenue factors play a crucial role in shaping project financing and overall investment returns.

Return on Investment and Financing Options

The rental income potential ties directly into financing options, and the CMHC's Apartment Construction Loan Program can significantly impact project viability. This program offers low-cost loans that cover up to 100% of residential construction costs for projects with a minimum threshold of $1,000,000 [6]. Both tall mid-rise and tower projects can benefit from this, helping to lower financing costs during development.

For projects meeting CMHC MLI Select standards, which require a per-unit cost of $200,000, financing covers 95% of costs with only a 5% down payment, paired with 50-year amortization periods. This favourable leverage - often described as a 20:1 ratio compared to traditional financing - can improve cash flow right from the start, even for projects with higher construction costs.

Additionally, Budget 2024 introduced $500 million for prefabricated construction and $100 million for developments above existing retail spaces. These funding streams can make both tall mid-rise and tower projects more feasible, especially when paired with modern construction techniques.

The CMHC Frequent Builder Initiative further supports experienced developers by offering priority resource allocation and expedited loan approvals. This can be especially helpful for complex tower projects, ensuring quicker project delivery.

From a financial perspective, tall mid-rise projects generally yield annual returns of 12% to 20%, thanks to their lower risk and faster construction timelines. Towers, while requiring more upfront capital and longer development periods, can achieve comparable or slightly higher returns due to their increased unit density. Integrated construction methods also help avoid the 30% to 60% cost overruns often seen in fragmented projects, providing the financial stability needed to effectively leverage CMHC programs.

Multi Family Design in Type V III Podium vs Type I High Rise Construction

Key Takeaways for Property Owners

When deciding between a tower or a tall mid-rise building, property owners need to balance upfront construction expenses with long-term rental income. Tall mid-rise buildings tend to be more straightforward, with construction costs ranging from $160,000 to $200,000 per unit and offering annual returns of about 12% to 20%. Their simpler designs often result in quicker construction timelines and lower risks.

Towers, on the other hand, demand a larger initial investment due to their complex structures, elevator systems, and parking requirements. However, they can maximize unit density within FAR limits, making them an attractive option for those looking to fully capitalize on available land.

When it comes to construction methods, fragmented approaches can inflate costs and stretch timelines. An integrated design-build approach - where planning, architecture, engineering, and construction teams operate as a single entity - offers fixed pricing and guaranteed timelines. This streamlined method can shrink construction periods to as little as six months, enabling property owners to start generating rental income sooner.

Financing also plays a major role in project feasibility. Programs like CMHC's MLI Select provide up to 95% financing with just a 5% down payment, offering property owners substantial leverage and improved cash flow right from the start.

Ultimately, property owners need to evaluate their risk tolerance and financial resources. Tall mid-rise buildings are ideal for those seeking predictable returns with less complexity, while towers may appeal to investors ready to commit more capital upfront for the potential of higher rental yields through greater density. Success hinges on minimizing coordination issues by aligning design, engineering, and construction under fixed costs and guaranteed schedules.

FAQs

How do CEN-2 FAR caps affect the choice between building a tall mid-rise or a tower in Nova Scotia?

CEN-2 FAR (Floor Area Ratio) Caps in Nova Scotia

In Nova Scotia, CEN-2 FAR (Floor Area Ratio) caps are a key factor in deciding whether a tall mid-rise or a tower is the right fit for a particular property. These caps regulate the total floor area a building can have in relation to the land size, directly influencing both the height and overall design of the structure.

Tall mid-rise buildings - typically over 20 metres but shorter than towers - are often a smart choice for smaller lots where FAR limits impose restrictions on height and massing. On the flip side, towers work better on larger properties with higher FAR allowances, enabling greater height and density while staying within zoning regulations.

Choosing between these two options comes down to land size, zoning rules, and investment objectives. FAR caps serve as a crucial framework for determining what’s feasible and shaping the design.

What are the financial benefits of using an integrated design-build approach for multi-unit residential projects?

Opting for an integrated design-build approach in multi-unit residential projects can bring notable financial benefits. On average, this method cuts overall costs by up to 6% and reduces cost overruns by about 5% compared to traditional construction methods. It also simplifies project timelines, helping to avoid delays and limit expensive change orders.

On the other hand, fragmented construction models often struggle with inefficiencies and miscommunication, leading to higher costs - typically 1% to 6% more - due to poor coordination among various contractors. With an integrated approach, property owners enjoy greater cost control, fewer unexpected issues, and a smoother, more predictable construction process. It’s a practical choice for those aiming to meet both financial and project objectives efficiently.

How do parking design choices influence costs and environmental impact in CEN-2 projects?

Parking design choices within CEN-2 zoning can greatly influence both project costs and their impact on the environment. For instance, underground parking tends to be more expensive due to the need for excavation and additional structural support. It also has a higher environmental cost, as the process relies heavily on concrete and consumes significant embodied energy, leading to increased CO2 emissions.

On the other hand, surface parking and structured parking present more economical and environmentally friendly alternatives. These options not only reduce upfront construction expenses but also help lower long-term operational costs, making them a better fit for projects aiming to meet sustainability goals.

Carefully planning parking solutions can strike a balance between environmental considerations and project feasibility, ensuring compliance with CEN-2 zoning requirements while optimizing resources.